By Patrick van Schie

65 years ago, an uprising against communist rule took place in Hungary. It was not the first uprising behind the Iron Curtain (in June 1953 an uprising took place in the GDR, in June 1956 in the Polish city of Poznan) but it was the largest. The Hungarian uprising was completely unexpected, for the Communist Party in the country itself and for the Kremlin as well as for the West. But it didn’t come out of nowhere.

After the Second World War, Hungary was ‘liberated’ from the Germans by the Red Army and thus immediately occupied. Ostensibly this country was left somewhat more liberal than the other later satellite states; in the autumn of 1945, for example, free elections took place in which the communists obtained ‘only’ 17% of the vote and the ‘bourgeois’ party of small owners no less than 57%. The communists then formed a minority in the national government. The Soviet Union (still) kept in check the Hungarian communists who wanted a more drastic sovietization. But in 1947 the country was equalized anyway. As elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe, the Communist Party became the sole ruler. In Hungary it was led by Stalinist Rakosi. Between 1950 and March 1953 (Stalin’s death in Moscow) alone, 4% of the Hungarian population was mostly sentenced to prison for political reasons (with false charges such as spying for the US or leading a “conspiracy against the people”) ; dozens of people were also executed.

After Stalin’s death, the Kremlin forced Rakosi to resign as head of government (but not party chief) and installed Imre Nagy as prime minister. Nagy was a convinced communist (and informer of the secret service of the Soviet Union, the NKVD, the predecessor of the KGB), but relatively reformist. He believed that the path to communism should be taken more gradually, for example by focusing less unilaterally on heavy industry (so that more goods would be produced for consumers) and by allowing smaller farmers to still have some private land. However, in early 1955, Nagy was deposed again. But after Khrushchev’s secret speech that heralded de-Stalinization in the Soviet Union (February 1956) and the uprising in Poznan, Poland (June 1956), the Politburo in Moscow changed its mind again. Rakosi was maneuvered to the sidelines. The new party leader became another hardliner: Ernö Gerö. On October 22, 1956, the relatively reformist communist Gomulka came to power in Poland, a fact on which the Kremlin appeared to acquiesce. One day later, a large demonstration took place in Budapest in which 200,000 people called for Gerö’s resignation and Nagy’s return to rule, as well as for free elections and withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact (established a year earlier); this was a military alliance that served to legitimize the continued presence of Soviet troops in the satellite states.

Nagy himself was completely taken by surprise by the events. At first, he did not even want to meet the protesters. But the next day he addressed a large crowd gathered in the square in front of it from parliament. How much Nagy did not understand what was going on – a spontaneous popular uprising – is apparent from his opening speech: ‘Comrades’. Whereupon the crowd cried, “We are not comrades, we are the people.”

For the first four days, Nagy, who was reinstated to his position as prime minister, did not know what to do with the situation. He was still a devout communist, and he strove with a reformist course towards a socialist society. On the street the demands were soon more far-reaching: in particular the return to a multi-party system with free elections, a free press and neutrality for Hungary (i.e. withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact). It was not until October 28 that Nagy gradually took over the demands of the street and formed a government that also included non-Communists. The Soviet troops began to withdraw from the capital (but not from the country). On October 30, Nagy announced in a radio address that the multi-party system was being restored and that Hungary would enter into negotiations with the Soviet Union about the total withdrawal of the Red Army from the country. That day, the Kremlin decided to acquiesce. This was announced one day later in Pravda.

But the very same day, October 31, Soviet leader Khrushchev changed his mind, and he had an eager Politburo from the CPSU behind him in Moscow to crush the uprising. From November 1, additional Soviet troops entered Hungary and maneuvered into strategic positions around the capital. The insurgents in Budapest meanwhile knew nothing (Nagy was aware but kept silent) and celebrated their freedom; which, unfortunately, would turn out to be short-lived. In the early morning of November 4, Soviet troops again entered the Hungarian capital and brutally put an end to the uprising. Janos Kadar, who was part of Nagy’s government and had voted for the restoration of the multi-party system and neutrality, committed treason and flew to Moscow during those days of apparent freedom. He was installed as the new Hungarian leader by the Kremlin after the uprising was crushed.

Nagy took refuge in the Yugoslav embassy with some loyal communists who had gone along with the demands of the insurgents. What he didn’t know was that the Yugoslav leader Tito, a communist who was not on a Moscow leash, had made a deal with the Kremlin. Nagy and his followers were extradited to the Russians in accordance with that deal. In a secret show trial, in which he nevertheless bravely defended himself, Nagy was sentenced to death on June 17, 1958, and executed the following day. As far as we know, between 1957 and 1959, between 350 and 400 Hungarians were executed for their involvement in the uprising. Another 39,000 others ended up in prison or in a camp, about 22,000 of them after a ‘judicial’ conviction (the rest without any form of trial or mock trial). Several hundred insurgents disappeared to the Soviet Union. In contrast, in the few weeks immediately after November 4, 1956, about 200,000 Hungarians (out of a population of 9½ million) managed to flee across the border into Austria to freedom outside Hungary. After that, the border was too closely guarded. About 50,000 of the refugees were taken in by the United States, just under 3,000 by the Netherlands.

The courageous struggle in Budapest reflected a very widespread aversion of the Hungarian population to the communist regime imposed on them. The Hungarians’ struggle for freedom, however, had no chance from the moment that the final decision was made in the Kremlin to crush the uprising rücksichtlos, that is, from 31 October.

The West watched in impotent fury all those days. In previous years, the United States had advocated ‘liberation’ of the satellite countries and the US Secretary of State Dulles had announced a ‘roll back’ policy, but the Americans had made no preparations in case one of the satellite countries would actually break out. For US President Eisenhower, the uprising was very inconvenient, in the final days of his reelection campaign. He was also preoccupied by the Suez Crisis, where Britain and France intervened militarily; a fact which the Kremlin eagerly took advantage of in order to be able to crush the Hungarian uprising in a relative media lee. This did not alter the fact that the population in various Western countries reacted furiously – with peaceful mass demonstrations, but in the Netherlands, for example, the CPN (communist party of the Netherlands) headquarters in Amsterdam were also pelted with stones – and that several countries boycotted the Olympic Games in Melbourne because of the presence of athletes from the Soviet Union.

But the Western countries were not prepared for a large-scale military encounter with the Soviet Union. The Hungarians and the other communism-sighed citizens of Central and Eastern Europe would have to wait for their freedom for 33 more arduous years (in the case of the inhabitants of the Baltic republics almost a year and a half longer).

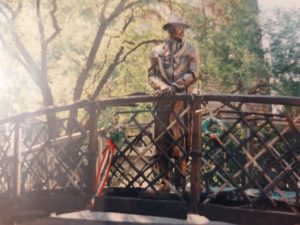

Image: monument of Imre Nagy, ©Patrick van Schie

Follow Us!