How the Poles saved Europe from the Red Army a century ago

Patrick van Schie

In Western Europe it is perhaps one of the least known battles of the twentieth century, yet one of the most important turning points: the battle of Warsaw in August 1920. Unexpectedly, the young republic of Poland defeated the Bolshevik Red army. What would have happened if this had turned out differently is a guess. But with the revolutionary attempts that took place in Germany after the First World War, there was a real risk that communism could have settled in the heart of Europe a century ago.

After the Bolshevik (= communist) coup d’état in Petrograd of October (according to our calendar November) 1917, Russia got into a civil war which lasted until 1920. At the same time, the Poles, whose country had been wiped off the map in 1795, saw an opportunity to regain their independence. At the end of the eighteenth century, Poland had been swallowed up by the three surrounding great powers: by Russia (which occupied the largest part, including the capital Warsaw), Prussia and the Habsburg Empire (which occupied a small part, including the city of Krakow). In the nineteenth century, the Poles had revolted several times. In the West they always got sympathy, but the Western European countries could not prevent these revolts from being put down by the Russians.

The end of the First World War gave the Poles the chance to have their own state, especially because the new European order was partly based on the principle of national self-determination thanks to the American President Wilson. In the peace talks of Versailles, the western and southern borders of Poland were thus demarcated, but the eastern border would depend on political and especially military developments there.

The leader of communist Russia, Lenin, decided in January 1920 that the new Poland should be attacked. At that time his regime was not yet capable of accomplishing it. The head of state of the new Polish republic, Pilsudski, decided in March of the same year to support one of communist Russia’s enemies, the Ukraine. This area also wished to establish its own republic, and Pilsudski saw it as a useful ally. He moved to Kiev, where the government of an independent Ukraine could be established. From the military point of view it was a success. Politically, it was less convenient for Western European countries. They now saw the Poles as aggressors, which made them less accommodating when the Poles became pinched a few months later.

Whether this really did matter much still remains a question, because public opinion in the West had long been exhausted by war. The Western countries had previously been reluctant to give serious support to the White (anti-communist) armies in Russia. Those White armies collapsed in the first half of 1920. Now Lenin’s decision of January 1920 could be carried out. In one month (early July to early August), the Red Army advanced about 600 kilometres to the west until it was located 20 kilometres from Warsaw. In fact, it was not so much a series of victories, but more an action of the Polish army that was a mixture of a retreat and a flag flight.

There was great panic, also in Western European countries, but especially in Poland itself. A Western diplomat described how he became trapped in the streets of Warsaw at the beginning of August amidst the many Catholic processions invoking the help of above against Bolshevism. Incidentally, the French in particular did send military advisers, including General Weygand, who would become commander-in-chief of the French army in 1940. However, he was kept at a polite distance by Pilsudski. There was also a young officer in the French military delegation, who observed closely, recorded his experiences and would later publish them. This young Frenchman became full of admiration for the Poles and their military achievements in August and September. His name was: Charles de Gaulle.

Near Warsaw, Russian forces led by 27-year-old Tukhachevsky met unexpected resistance from a Polish army led by General Sikorsky, the man who would be Prime Minister-in-exile in London at the time of World War II. Sikorski even managed to push back the Russian troops. Further south, Pilsudski pushed on to an area to the east of Warsaw, trapping part of the Red Army. Now it was the turn of the Red Army to flee disorderly. Within a month the Russians were driven from the area of present-day Poland. By mid-October – when a truce was signed – the Red Army had lost 200,000 men.

The miraculous turnaround – “the miracle of the Vistula” (a river that flows through Warsaw, among others) – prevented the Red army from invading Europe further. For the time being, the communists remained within the borders of Russia, where they were forced to focus on the realization of “socialism in one country”. But what was the purpose of their advance in July 1920? Russia expert Orlando Figes believes it was a “defensive” move; a “defense” at the expense of the new Polish state. Figes, however, is with his vision almost alone among historians. A series of famous historians – including Richard Pipes, Adam B. Ulam, Helène Carrère d’Encausse, Robert Service, Robert Gerwarth, Adam Zamoyski – do call the attack by the Red Army an attempt to spread the revolution to Poland and beyond in Europe, at least to Germany.

This was also the motto under which Tukhachevsky ordered the Red Army to advance on July 3, 1920: “The time of reckoning has come. In the blood of the defeated Polish army we will drown the criminal government of Pilsudski. Turn your eyes to the West. In the West the fate of the World Revolution is being decided. Over the corpse of Whte Poland lies the road to World Conflagration. On our bayonets we will bring happiness and peace to the toiling masses of mankind.The hour of attack has struck. WestwardOn to Wilno, Minsk, Warsaw-Forward!’’

What the communist regime lacked was their support among workers elsewhere. The Polish workers (and peasants) did not welcome the Red Army enthusiastically. Their patriotic feelings for the newly liberated Poland from the Russian yoke made them take up arms, urged on by the Catholic Church that warned against ungodly communism. They did not oppose their supposed bourgeois oppressors but the oppressors they had known for one-and-a-quarter centuries: the Russians.

What is more, Tukhachevsky’s attack was not supported by the part of the Red Army that invaded the south of Poland. The “political commissar” of this army unit – each unit had such an observer assigned to exert political control over the military commander – did not grant Tukhachevsky the credit of spreading the world revolution. This particular political commissar decided to ignore the orders he received from Moscow and to turn the attention of his army unit to Vienna and Budapest, followed by the main prize: Rome. If he succeeded in conquering Rome, he thought he would receive the laurel wreath. However, he did not achieve this in the slightest, but what he did achieve wat the fact that the Russian attack on Warsaw was seriously weakened. The name of this ambitious political commissar? Joseph Stalin.

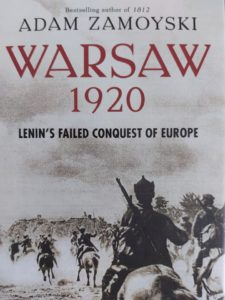

Suggested literature

A good book devoted entirely to “The Miracle of the Vistula”, as well as its run-up and how the protagonists fared, is: Adam Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920. Lenin’s failed conquest of Europe (London, 2008).

Image: painting by Jerzy Kossak ”The Miracle of the Vistula”.

Follow Us!